Heritage Impact Assessment using QField¶

From QGIS to QField and Vice Versa: How the New Android Application Is Facilitating the Work of the Archaeologist in the Field.

Roberto Montagnetti1 and Giuseppe Guarino2

† Presented at the ArcheoFOSS XIII Workshop—Open Software, Hardware, Processes, Data and Formats in Archaeological Research, Padova, Italy, 20–22 February 2019.

Abstract: The aim of this paper is to highlight the main benefits of using the QField app in archaeological jobs. In particular this article provides examples to use QField in open area excavation, Archaeological survey and impact assessment (HIA) projects.

Keywords: QField; archeology; VIARCH; HIA; QGIS

1. Introduction¶

The aim of this paper is to highlight the main benefits of using the QField app. An App that can be installed on an Android device for all archaeologists working in the field.

The main feature of this new application will allow the archaeologist to upload to his/her smartphone or tablet the .qgs project of the excavation based on the general information concerning the site that is already available to you. At this point, it is possible to implement the collection of data directly on site, maintaining constant updates to your system, thus allowing you to review the project throughout the excavation process.

The “pocket-GIS” with QField is finally a reality!

Working with QField in the field allows us to significantly reduce registration and computerization time of inputting data into the database system, eliminating the digitisation of field registers and all related paperwork. The advantage of entrusting all of the information to the main GIS platform of the project (master), which is stored inside the PC, means this leaves only the task of checking the collected data, along with the bonus of in-depth topographical and geospatial analysis.

In this article, we will show a practical example of integrated use of QGIS and QField, which relates to an open area excavation.

The intervention methodology proposed in this article was constructed by the personal experience of the authors; this specifically refers to open area excavation works in commercial archaeology projects.

2. Main Features of QField¶

QField is an Android app that can be downloaded from Google Play. This application, although it presents itself with a very simple interface, is rich in functions such as:

- Tools for digitalisation in the field;

- Geometry and attribute editing;

- GPS;

- Possibility to upload custom base maps;

- Integration of smartphone/tablet’s camera;

- Many other functions

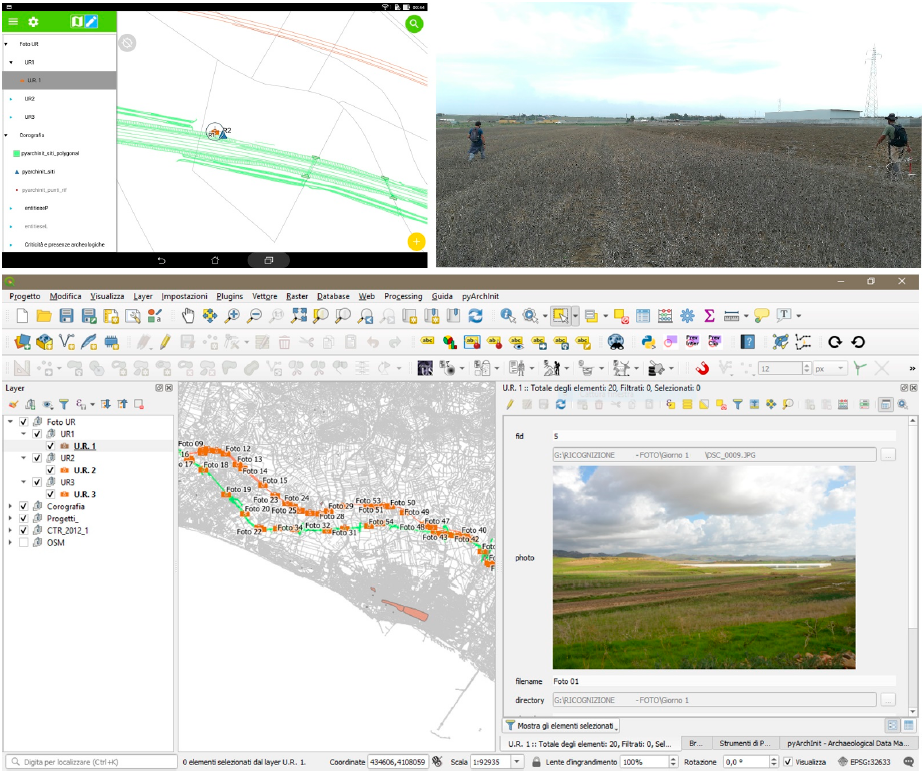

QField can be considered a “mobile” extension for QGIS. In fact, it allows us to view and manage a GIS project created with QGIS on an Android smartphone or tablet. Permitting the user to keep all set themes, labels and styles that are in the original project (Figure 1).

Furthermore, similar to QGIS, we can query each layer within QField by obtaining the respective information contained in its attribute table (however, there are also other GIS applications for mobile such as ArcGis, LiPAD, Bentley Map Mobile, GVSig Mobile, Geopaparazzi and others).

In order to work with a QGIS project within QField, the first step is to configure the properties of that project created in QGIS as “save relative paths”.

You will need to create a folder “folder_name” on your desktop and save in this path the .qgs file that you want to transfer to the smartphone or tablet; similarly, in the same folder, you have to enter all the data (vectors, raster and database) that make up this QGIS project.

These data can also be divided into further subfolders.

Finally, you need to copy the entire folder ‘folder_name’ to the tablet, following two possible paths:

- In the internal memory: Android > data > ch.opengis.QField > files > share;

- In the external SD: Android > data > ch.opengis.QField > files.

3. Working with QField in an Archaeological Survey and Archaeological Risk Assessment Projects¶

Until recently, paper maps were the only way of recording archaeological features and the fields’ visibility in an archaeological survey work. Such data were digitised into a CAD or GIS software creating the individual site sheets separately on a simple digital document afterwards.

Today, QField, thanks to its compatibility with QGIS, allows you to skip the transition from paper to digital or from different software, reducing time and costs.

The archaeological survey (for a comprehensive account of methods of the Archaeological survey, see Cambi, Terrenato 1994, pp. 117–143, and Renfrew, Bahn 2016 [1,2]) must be preceded by the construction of a GIS platform that takes into consideration both the data acquired during the field survey phase and the bibliographic ones. For this reason, it will be necessary to work on two tables:

- One is spatial, which is useful in the field.

- The other is alphanumeric.

Both will be joined in a single spatial table, useful for consultation on the GIS desktop. This process is possible through the use of a relational geo-database such as SpatiaLite and PostGIS or, alternatively, through the creation of a join between the tables and the geometries.

However, the big advantage of using a geo-database is the ability to create queries capable of merging information from two or more tables into a single table (view) (for more in-depth information on the use of GIS and Geodatabases in archaeology, see Fronza, Nardini, Valenti 2009 [3]).

This process further speeds up field work by minimising the data to be stored during archaeological survey.

The data collected in the field during the survey will be recorded and digitised through three different layers (point, line and polygon). The attribute tables connected to the three layers record the following information: Project Name (String), Municipality (String), Location (String), Feature Number (Integer), Place Name (String), Location (String), Date (Date), Site Definition (String), Visibility (String) and Photos (String).

The attribute values, “Project name” and “Feature Number”, between the two tables must be Unique Constraint in order to identify only one unique “Project name” and only one “Feature Number”.

The GIS platform must also have base maps such as Google Satellite, Open Street Map, Orthophotos and so on. In this case, we used the following maps: Carta Tecnica Regionale (1:10.000), Open Street Map e Google Satellite. To make these maps lighter, we created first overviews (pyramids) in QGIS.

The positioning of the archaeological features identified can be recorded through the GPS internal device. However, for a greater accuracy, QField can be connected to a GNSS antenna.

In archaeological consultancy and archaeological risk assessment jobs, it is recommended to upload into the GIS project an infrastructure layer containing the infrastructure’s geometric information, measurements and others, besides a buffer of itself.

After setting the basics of our project on QGIS, we need to export the project through the use of the QFieldSync plugin within QField. Alternatively, we can carry this out by simply copying the folder containing the project file with the *. QGIS extension, the database and the rasters (or the GeoPackage containing our rasters: IGM, Basemap and so on) into our smartphone or tablet.

By default, QField creates a folder where you can save projects (Android/data/ ch.opengis.QField/files), but it is always better to store them on an external SSD, since if you were to uninstall QField from your device, all the folders and files contained in them will be removed running the risk of deleting the data.

After we set up the bases of the GIS project in QGIS, we need to export it into QField through a suitable plug-in called QField-Sync.

However, we can perform that task even by simply transferring (copy and paste) the QGIS project and the related dataset to our Android device. The QGIS project must be saved as .QGIS.

4. Benefits and Drawbacks of Using QField in an Archaeological Survey and Archaeological Risk Assessment Jobs¶

QField, similar to all the cutting-edge tools, has some limits related the the use of the devices; the main one of these might be caused by the poor bandwidth or lack of internet. In this case, we cannot have a good accuracy in the registration of our archaeological features by using the GNSS. At the same time, we would not to be able to upload WMS services such as Google Satellite, Open Street Map and others. Another disadvantage is related to the battery life: keeping the screen, data connection and GPS always active will drastically reduce the battery life of our device, even if we might bring with us portable powerbanks. On the other hand, the benefits of using QField are a lot; in fact, it allows us to reduce many procedures we were to carry out had we registered the archaeological features identified during the survey on a paper map or had we filled up their related information manually on paper sheets. Furthermore, another benefit constitutes the possibility of using QField for integrating the device camera or a GNSS antenna. All of this makes the collection of data easier and increases their accuracy while at the same time reducing time, costs and workforce.

G.G.

5. Working with QField in an Open Area Excavation¶

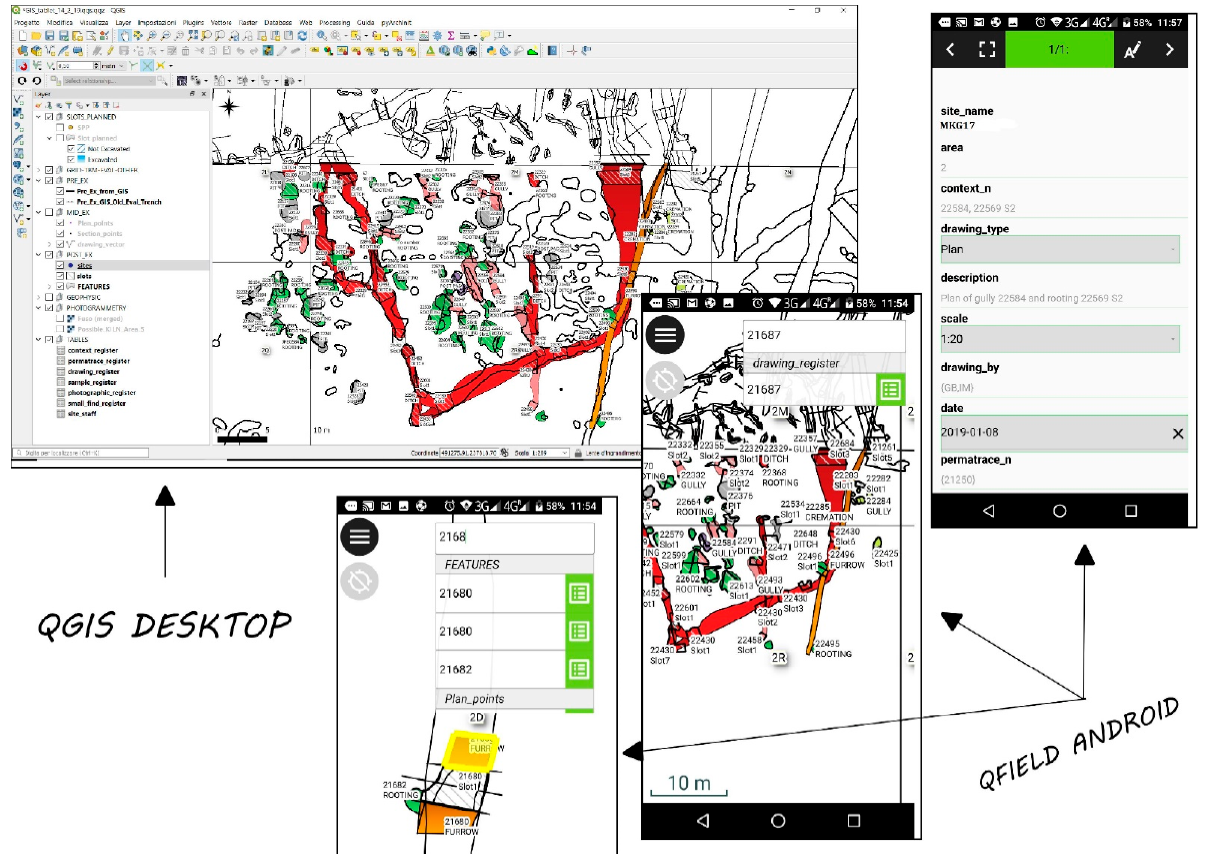

In an open area excavation scenario, the advantages and convenience of using an App such as QField are innumerable. This is true especially in commercial archaeology sites, where very often the deadlines to carry out the work and the budgets available for the archaeological investigation are very tight. This forces you to work with the maximum optimisation of the timing and assets, despite the fact that the weather and visibility conditions in the field are often poor (Figure 2).

Now, let us see why the use of QField facilitates the reduction of working times and, at the same time, guarantees the saving of resources to be invested in the archaeological investigation, providing a practical example of using the GIS App for Android.

In this kind of work, the first step is to strip the area to be investigated with the use of machinery, aiming to remove the topsoil and then eventually the subsoil.

The subsequent step involves the identification of archaeological features both directly in the field and by comparing the results of the aerial remote sensing and geophysical analysis when this type of technology is used.

The archaeological features identified are then digitally detected by GPS or Total Station.

Finally, all the excavation interventions that need to be completed in the investigation area (slots) are outlined, where it is more relevant in terms of understanding the stratigraphic relationship between the archaeological features identified.

This phase of the work is called “Pre-Ex”.

The Pre-Ex survey will be the topographical base for the creation of the GIS platform of the project in QGIS, together with the base map of the area, the TBM’s and any aerial orthophotos of the site. Within the same platform, we will also upload a geodatabase containing the layers necessary for the digitisation of the following:

a. The archaeological features identified in the field;

b The slots planned;

c. The contexts investigated and their related levels;

d. The plan and section lines used for the manual drawings;

e. All the elements that we may need to detect during the archaeological investigation of the site.

However, in the same database, there will also be tables related to the paperwork sheets.

Thus, they are comparable to the digital version of the paper registers and other related paperwork that are commonly used on construction sites for excavation documentation.

This database (what comes next is just an example of database structure. Tables and geometries can be different according to the characteristics of the sites and the topology of investigations that must be carried out. In any case, tables and vectors must be related to each other in order to interact. QField recognises the project relations set in QGIS.) is made of:

- Sites (Vector): Contains the list and description of all the sites on which the company is working.

- Context_Layer (Vector): This layer graphically represents all the contexts identified and excavated during the excavation project.

- Slots (Vector): This layer graphically represents all the slots excavated and contains the information of the paper slot register.

- Level_Layer (Vector): This layer graphically represents all the levels taken during the excavation of each slot.

- Drawings_Vector (Vector): This layer graphically represents the plan and section lines used for the manual drawings.

- Drawing_Point (Vector): This layer graphically represents the points through which the plan and section lines pass.

- Context_Register (No geometry): digital register, which contains all the investigated contexts.

- Drawings_Register (No geometry): digital register of all the drawings.

- Permatrace_Register (No geometry): digital register of the permatrace sheets.

- Sample_Register (No geometry): digital register of the samples collected.

- Photo_Register (No geometry): digital register of all photos taken.

- Small_Find_Register (No geometry): digital register of all small finds collected.

- Finds_Bag_Register (No geometry): digital register of all finds bags collected during the excavation.

- Context_Sheets (No geometry): This layer is the digital version of the context sheets register and contains all the information related to each context investigated.

At this point, we need to simply transfer the master project created in QGIS with all the “project relation” and “widgets” to the tablet or the smartphone and manage it directly on site with QField to immediately appreciate its advantages and convenience (Figure 3).

In fact, primarily, by using this system, archaeologists who are working in the field will be able to directly register the context numbers identified during the excavation within QField, in the appropriate “context register” table in the QField database.

This aspect already speeds up on-site operations by saving the time generally taken to go back and forth from the site to the compound or from the site to the car/van and vice versa, for the compilation of paper registers; especially, if we take into consideration the fact that, on a regular basis, cars and compounds are located at a considerable distance away from the excavation area.

Additionally, since generally there is only one device on site and this is usually held by the site manager or by the supervisors, this would make it easier for them to check that the field archaeologists are assigning the right numbers to the identified contexts.

Very often, on a location tend to become confused, especially when the excavation area of the site is poor due to adverse weather conditions. Along with the above issues, they can also encounter errors such as registering the same feature with different cut numbers or by assigning the same context numbers to different features.

This occurs even more frequently when the field team is composed of numerous archaeologists who work in separate excavation slots from each other. These slots can be spread around the excavation area, making interaction and communication between them more challenging.

This issue is also linked to another problem, which means, for those who work in the field, it is impossible to have a constant overview of the investigation area and the archaeological features identified, which often causes confusion and making mistakes during the registration of the context numbers.

Therefore, from this point of view, QField represents a real breakthrough by giving the following possibilities to the people working on site, at any time:

i. To have a general overview of the excavation area;

ii. To query the surveyed archaeological features;

iii. To check the shape and the orientation of the archaeological features identified in the Pre-Ex phase, which must be dug even when the site conditions are poor.

QField aids with various challenges encountered in the field: time wasted due to inclement, wet weather and perpetually sodden and muddy soil churned up by people and vehicles continually accessing the site. These cause the identified archaeological features to become unrecognisable after several days of the site being stripped (Figure 2).

By using the device’s GPS, as it allows the user to navigate within the excavation area and to find, albeit with a certain margin of error, the archaeological features that need to be excavated, even when the visibility on site is poor.

Similarly, by doing so, when visibility conditions are bad, it is easier to centre with the slots in the archaeological features that have previously been identified in the Pre-Ex phase, which prevents the miscalculation of digging into the natural sites.

A typical example of this is when there are furrows running across the field, and it becomes increasingly difficult to see their entire length with the naked eye.

Typically, in order to remedy this type of problem, archaeologists use printed maps in the excavation area; however, although this can certainly be a help, in practice, they are in no way comparable to the convenience of digital maps and consequently to QField for a number of reasons:

- Printed maps deteriorate very quickly due to wind, humidity and especially when handled by human hands.

- To contain the entire excavation area, they must often be printed in very large formats, which requires particular plotters, which incurs considerable costs and makes them difficult to use.

- Paper maps are not interactive, which means that you cannot ask them questions.

- They do not solve the problem of having to precisely centre the archaeological features, which need to be investigated with the slots when the visibility conditions on the site are poor.

Notably, the use of QField on site simplifies the workload of managers and supervisors in the planning of the excavation interventions, allowing them to easily instruct field archaeologists directly in the excavation area. By doing so, they will be able to train the field team efficiently with accurate information regarding the features that they will have to dig, supporting their explanation with the graphic aid of the tablet and with details related to what has already been investigated and uploaded into the database of the project.

Apart from the fieldwork, QField makes the job easier for archaeologists even in the recording phase, simplifying their work in the production of the paperwork. As we already mentioned, they can continuously query the tablet to obtain the necessary information that needs to be included in their paper documentation sheets, such as the section or plan numbers of the contexts that they have excavated, along with the photo numbers of the same contexts, or any other related information.

Furthermore, it will be much easier for them to draw the location plans that are generally required in the context sheets, as they will have much more pieces of information available to provide an interpretation of what they have dug.

Another very important aspect to take into consideration when working with QField is that there is a possibility of completely removing the manual registration process of the slot numbers, context numbers, drawing numbers, sample numbers, photo numbers and so on. Simultaneously, by using this system, we can also avoid issues such as:

- The manual data-entry of the paper registers into the database of the project;

- The problem of deciphering incomprehensible calligraphies, which greatly increase the possibility of making transcription mistakes.

In fact, unclear calligraphies are a recurring problem related to the manual recording of the excavation documentation and in particular of the registers. This is also going to affect the accuracy of the information that must be put into the database during computerisation.

Additionally, the archaeologist involved in the paperwork must include in his documentation context numbers, drawing numbers and other types of information related to the archaeological features and in relation to his own, which have been excavated and recorded by other colleagues. In this circumstance, to confuse one number for another, perhaps due to the unclear handwriting of the colleague, is a very common mistake.

Worst-case scenario means that:

- There will no longer be a match between digital registers of the database and paper registers;

- The information on various context sheets will not be reliable;

- Both cases (as mentioned above).

Therefore, we will have to spend a lot of time and effort tracking down the error and correcting it.

Instead, the use of a digital recording eliminates this problem and facilitates the checking of errors.

The main benefit of the GIS tools is that they enable us to query the features by giving us the possibility to cross-check data, which speeds up the checking process.

To give a practical example, if you need to adjust the number of a context, or a drawing or anything else within a digital register by a number, with the QGIS “field calculator”, it becomes an easy task taking only a few seconds.

Just think how long it would take to perform the same task using registers and paperonly documentation, especially when working with considerable amounts of data collected within an extensive excavation.

In this case, you must first trace the folder containing the numerical series of the number to be revised, then browse one-by-one all the registers until you find the number that needs to be amended and finally corrected, along with all the subsequent numbers. This will not only need to be corrected in the registers, but also within the specific sections of the context sheets.

In other words, if a context, drawing or photo number has been registered incorrectly, it is not enough to correct only the register but also all the paperwork that relates to the number that has been mentioned.

Therefore, by using a digital register (table), the operation will only take a few minutes; however, if you were working on the paper documentation by hand, it could take numerous hours of hard work.

One final significantly important aspect to take into consideration is the saving of paper and consequently the amount of money involved. The use of QField and digital documentation allows us to efficiently manage the excavation data. By working in this way, it is no longer necessary to print out the survey plans, the registers and the paperwork sheets.

However, if the competent authority (county archaeology) or the customer explicitly requests a paper version of all the documentation produced on site, it will be possible to print out everything at the end of the project, only once all of the amendments have been made. This helps to avoid unnecessary waste of paper, along with all the other problems that were previously mentioned.

Even in this case, the QGIS “print composer” allows us to develop customised layouts that can be saved and used at any time.

6. Conclusions¶

In an increasingly digital world, it is unacceptable to continue working on paper especially because, at the end of the process, all paper documentation must be digitised for archiving needs. Today, in fact, both the museums and the warehouses of the archaeological companies have less space available for the storage of paper folders. At this point, it would be beneficial to manage the data in a digital format at the beginning of the excavation process, immediately saving time and resources.

Scanning the PDF documents of registers, context sheets and, in general, all documentation produced on site is not a practical and sustainable solution. As previously mentioned, often, this documentation in extensive excavation projects is made up of thousands of paperwork sheets; I challenge anyone to reconstruct an excavation matrix by checking all the stratigraphic reports on the paperwork PDF scan. This kind of job forces you to continually scroll up and down the PDF document in search of the relationships between the various contexts, resulting in a significant waste of time and energy; without any regards to the costs that are involved when scanning in thousands of sheets.

Archaeological excavations are constantly driven by strict and increasingly shorter deadlines. The use of GIS for the management of excavation data can no longer be ignored. Currently, the possibility of an “Open Source” and a “pocket” GIS platform, such as QField, truly represents a unique opportunity to make the work of archaeologists on site easier, faster and more accurate.

As previously mentioned, it is much easier to build the matrix and compile the phasing of the archaeological features identified working with a digital system during the Post-Ex phase. Thus, only an instrument such as GIS, which gives us the possibility of launching queries and continuously cross-referencing data, allows us to perform this type of work quickly and efficiently.

At the same time, the GIS allows us to have a continuous overview of the data produced on site and to further implement information regarding the investigation by using geospatial analysis, which helps to facilitate the final interpretative reconstruction.

In short, the principle of paper lasting forever cannot be accepted any more. Primarily, because it is not true, and secondly, it deteriorates over time, especially when, as in most cases, it is kept in the basements of archives, museums or sites of archaeological companies.

In addition, paper documents entail enormous logistical difficulties in terms of sharing and consulting data, in comparison to digital documentation, which can be easily shared.

R.M.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

References

- Cambi, F.; Terrenato, N. Introduzione All’archeologia dei Paesaggi; Carocci Editore: Roma, Italy, 1994; pp. 117–143.

- Renfrew, C.; Bahn, P. Archaeology, Theories, Methods, and Practice. Archaeol. J. 2016, 148, 329–330.

- Fronza, V.; Nardini, A.; Valenti, M. Informatica e Archeologia Medievale: L’esperienza Senese; All’insegna del Giglio: Firenze, Italy, 2009.